Back in July, I started a project to repair my aging PowerBook G3 Wallstreet for a third time. I was not the original owner of this PowerBook and I had successfully completed two other repair attempts. Alas, the third time was not to be a charm and I decided to end the project.

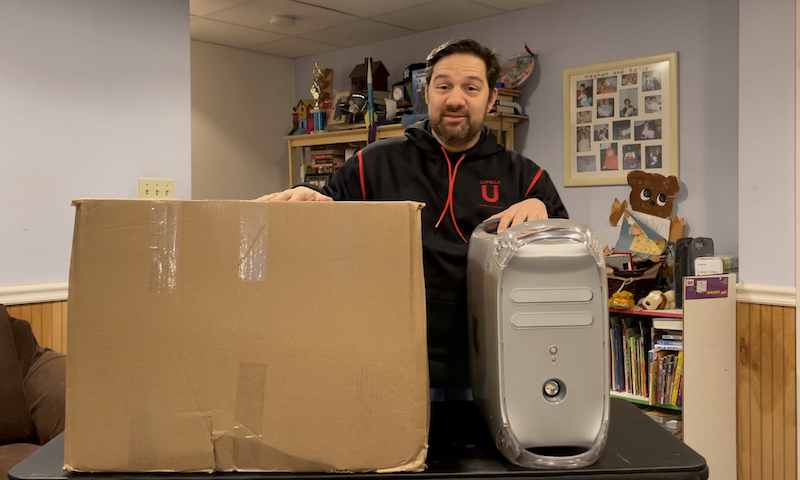

Still wanting to have a vintage Power Macintosh with an Apple Super Drive 1.44MB floppy disk drive, I turned once again to eBay to find something to replace my Wallstreet. Enter the Power Macintosh 7200.

Introduction of the Power Macintosh 7200

The Power Macintosh 7200 was the low-end of a trio of new Macs that were introduced at Macworld Expo Boston in August 1995. The 7200’s siblings are the Power Mac 7500 and 8500. These machines had been released at a time when Apple needed to release speedier machines to compete with Windows NT machines running Intel Pentium processors. According to Anita Epler, writing for InfoWorld at the time, these machines offered three advantages over the previous year’s Macintosh models: fast PowerPC 601 (7200/7500) and 604 (8500) CPUs, including PCI expansion card slots over the proprietary NuBus slot, and competitive price cuts. Epler spills the codename info by stating that internally, Apple referred to this wave of Macs was “Power Surge” and included the monikers “Nitro” (8500), “TNT” (7500), and “Catalyst” (7200).

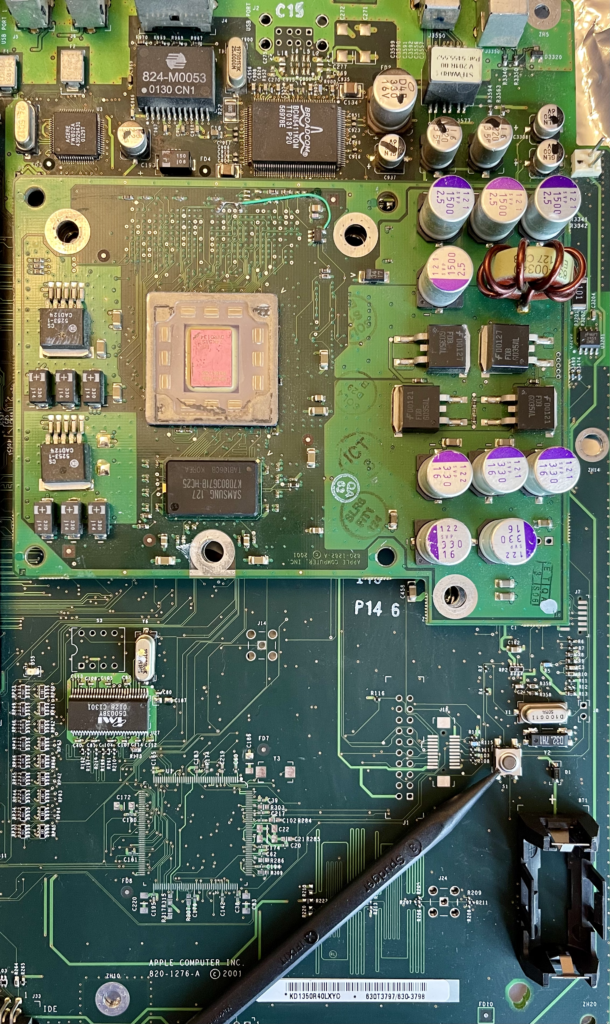

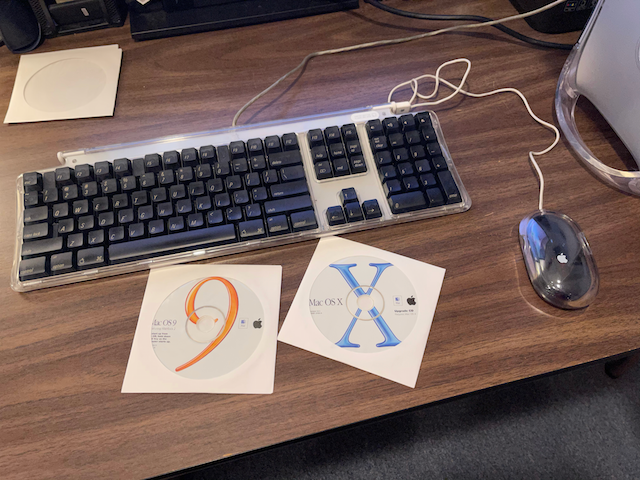

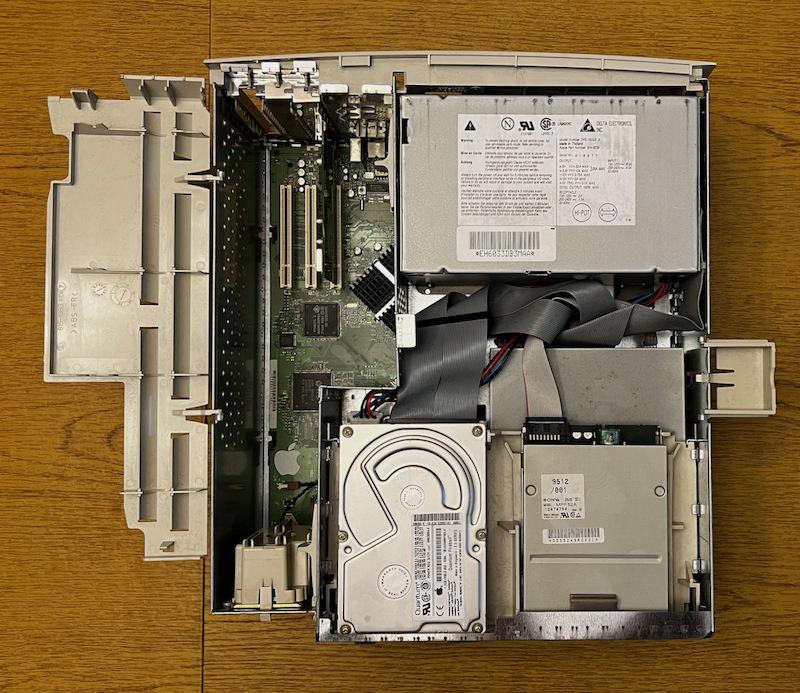

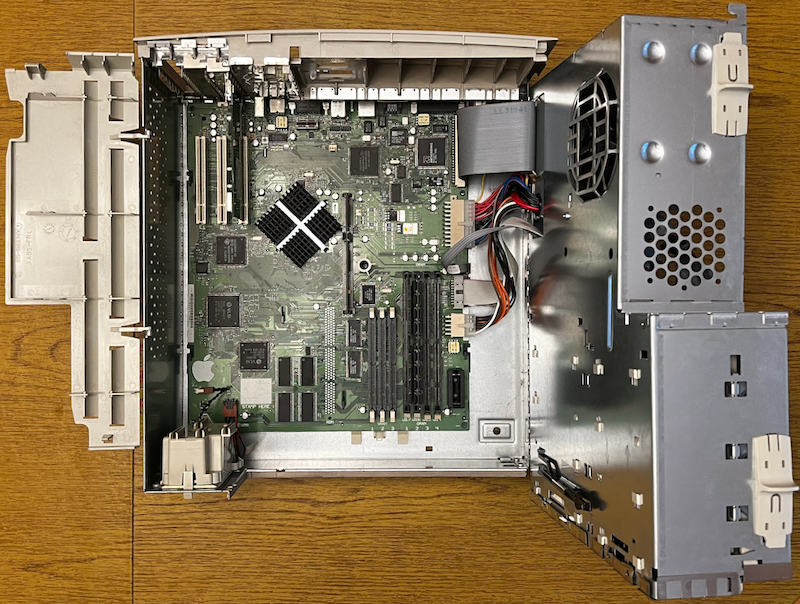

Even as the low-cost model of the bunch, the Power Macintosh 7200 included the same design language – and parts – as the 7500, which should have made it cheaper for Apple to produce. Available in two CPU speeds, 75 and 90 MHz, the 7200 started at $1,699. The CPU was later spec bumped to 120 MHz in April 1996. In addition to the 1.44MB Super Drive floppy drive that could read/write Macintosh and MS-DOS/Windows floppy disks, customers had an option for a 4x or 8x CD-ROM optical drive and a 3.5-inch 500MB to 1.2GB SCSI hard disk. On the motherboard, which was easily accessible by way of a novel swing-out chassis, there are four 168-pin DIMM slots accepting up to 512MB of RAM. There are also four graphics memory VRAM slots, which came populated with a 1MB chip. Finally, these Macs featured a 10Base-T RJ-45 Ethernet port for a direct network connection. If you needed a different network media type, customers could either add a PCI network card or use an AAUI network adapter, such as the Farallon Etherwave transceiver. I was happy to ditch the Etherwave that I had to support on the Power Macintosh 7100. Unlike its siblings, the Power Mac 7200 lacked a processor upgrade slot.

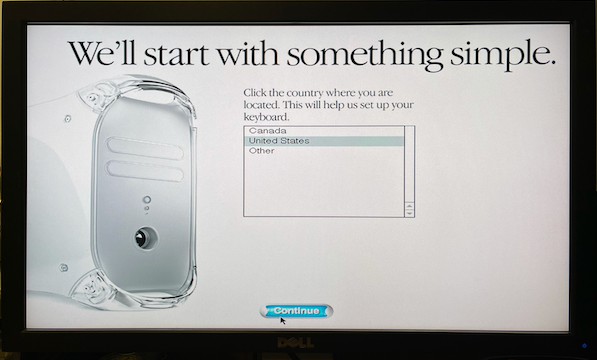

Looking the Power Macintosh 7200 up in Ian Page’s excellent Mactracker app (macOS and iOS/iPadOS), we see that the 7200 can run Classic Mac OS System 7.5.2, with a machine specific enabler, all the way up to Mac OS 9.1. Support for three versions of Classic Mac OS is a pretty good run, however, I wish that Apple had provided an upgrade patch to reach the last version of Classic Mac OS, v9.2 released in June 2001.

The full Power Macintosh 7200/120 specifications are still listed on the Apple Support website.

A Success Despite Serious Leadership Dysfunction

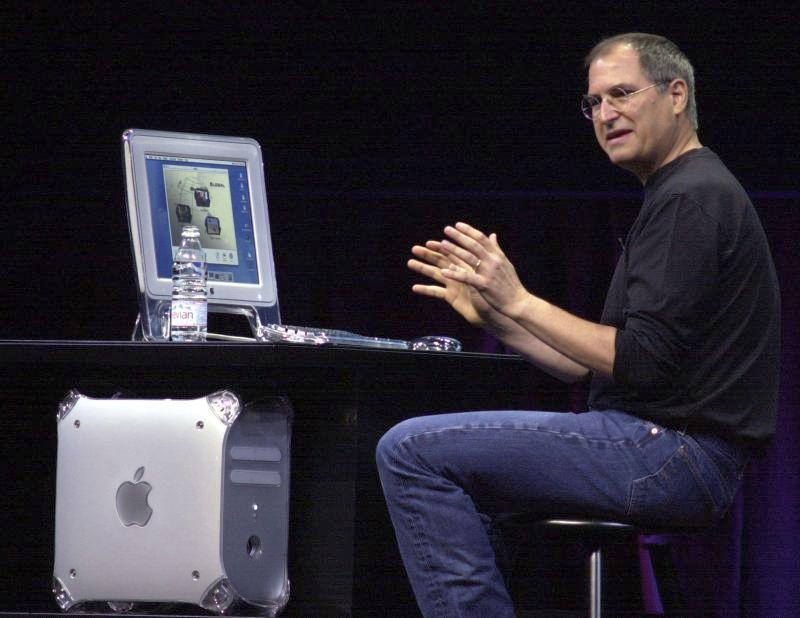

In 1995, Apple was heading into serious financial trouble, and it would still be a few years before the NeXT acquisition that would bring Steve Jobs back to Apple.

The Power Surge line of Macs were developed and released near during then Apple CEO Michael Spindler’s tenure (1993 – 1996). Tom Hormby, writing for LowendMac.com, remarks that Spindler was regarded inside Apple as “brilliant strategist” and had a great deal of success running the Apple Europe division. However, once promoted to the executive ranks, Spindler suffered from “debilitating levels of stress”. Despite the many technical and management problems Spindler faced at Apple, the PowerPC collaborative project with Motorola and IBM had come together. The Power Macintosh 7200 benefitted from the PowerPC 601 CPU that came out of that collaboration. After a disastrous performance at the annual shareholder meeting on January 23, 1996, Spindler was replaced by Gil Amelio, who would go on to start serious discussions about the NeXT ‘acquisition’ in late 1996.

Throughout all the turmoil inside Apple in the 1990s, engineers were able to release a well performing machine. A beige box Mac that, in my opinion, includes design queues from the Macintosh SE with its grill vents alone the sides and the Mac Classic with its rounded face plate. The Power Macintosh 7200 and 7500 also featured an easy to remove case that slide off, just like the older compact Macs. Apple would continue to release beige box desktop and tower computers for a few more years until Steve Jobs and Jonny Ive would release the colorful Bondi Blue iMac with a 233 MHz PowerPC 750 G3 processor.

Other Configurations of the 7200

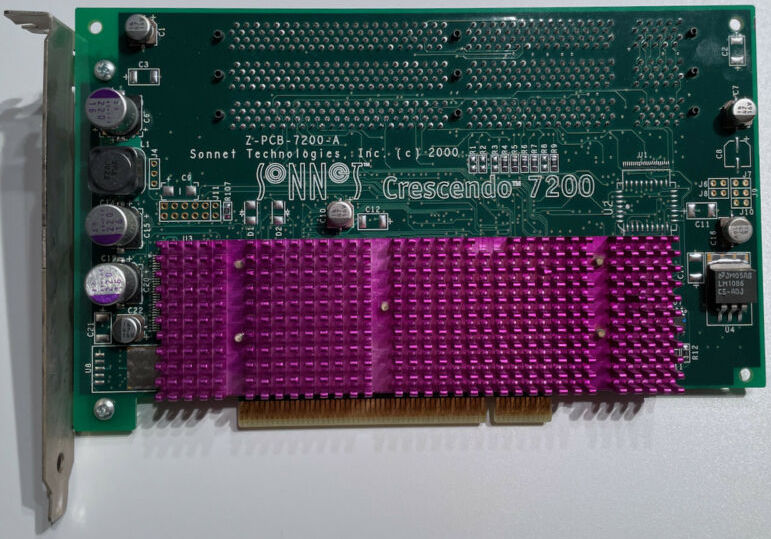

The Power Macintosh 7500 and 8500 featured a slot on the motherboard for a CPU daughter card. The purpose of this card, in part, made it possible to upgrade the Mac later on with a fast CPU. The 7200, however, lacked the modularity of the other two Power Surge machines.

After the PowerMac 7200 was discontinued by Apple, Sonnet Technologies developed a PCI processor upgrade board called the Crescendo/7200 G3. The Crescendo PCI board is compatible with the Power Macintosh 7200 and the Power Macintosh 8200; a tower version of the 7200 that was released in April 1996. The upgrade board includes a 500 MHz PowerPC 750 G3 CPU with 1MB of backside cache. Crescendo also came with three 168-pin DIMM slots allowing customers to upgrade to a total of 768MB when three 256MB DIMMs are installed; a significant upgrade over the 256MB RAM maximum over a stock 7200. At somepoint in my Power Macs past, one of these Sonnet cards was installed, because a Powered by Sonnet sticker was affixed to the case. The card was removed before I purchased it, so I scraped off the label with a plastic spudger.

According to EveryMac.com, Apple also released a “PC Compatible” version of the 7200/120 that included an Intel Pentium PCI card that enabled the machine to run MS-DOS and Windows operating systems. There was also an enterprise server version of the machine, known as the Power Macintosh Workgroup Server (WGS) 7250/120. Both variants shared the same case as the Power Macintosh 7200-series desktop PCs.

Using My Power Macintosh 7200

The Power Macintosh that I purchased, a 7200/120 model, came with the previous owner’s applications and documents still on the hard drive.

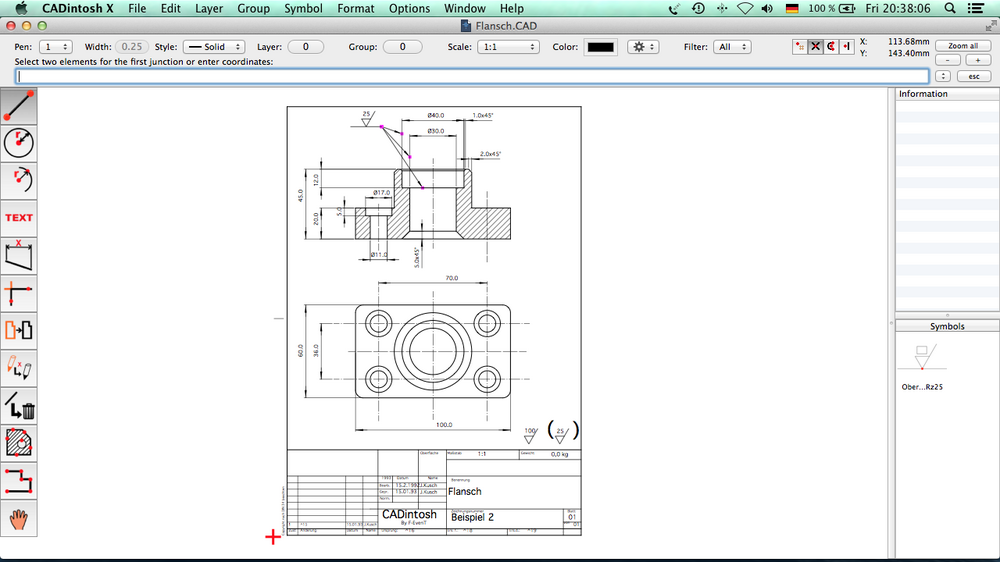

Interestingly, it appeared that this Mac was used at a business that did engineering work based on the registered install of LemkeSoft CADintosh and the documents that I reviewed before wiping the disk drive clean and reinstalling Classic Mac OS 9.1. I had never heard of CADintosh before. Interestingly, LemkeSoft is still releasing versions of CADintosh for Intel and Apple Silicon Macs. If so inclined, you can purchase a copy of CADintosh for $32USD or $30 Euros.

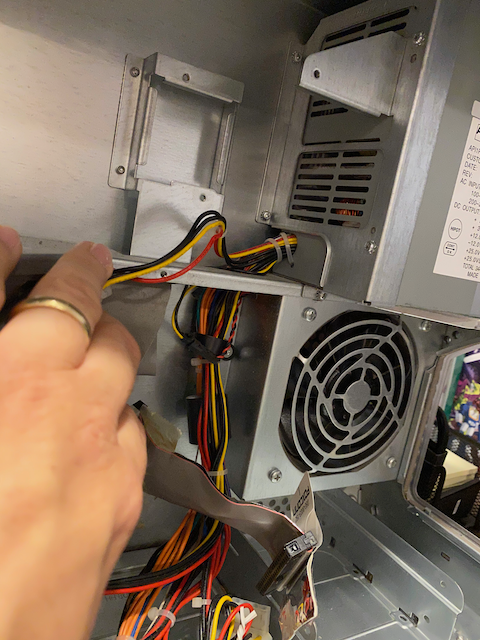

In my experience restoring the 7200, I can atest to the speed boost of this old machine. Mac OS 9.1 feels zippy on this computer and Quantum Fireball SCSI 1.2GB hard drive doesn’t feel like the performance bottleneck that the Maxtor IDE hard drive was in my restored Power Macintosh G4 Quicksilver. I had originally planned on installing a Rabbit Hole Computing SCSI2SD v5.2 bridgeboard, but I decided to hold off for now and use the board for a Macintosh SE restoration project.

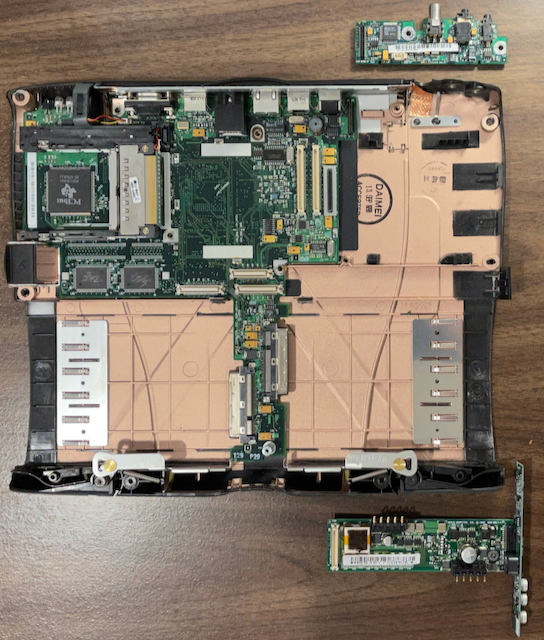

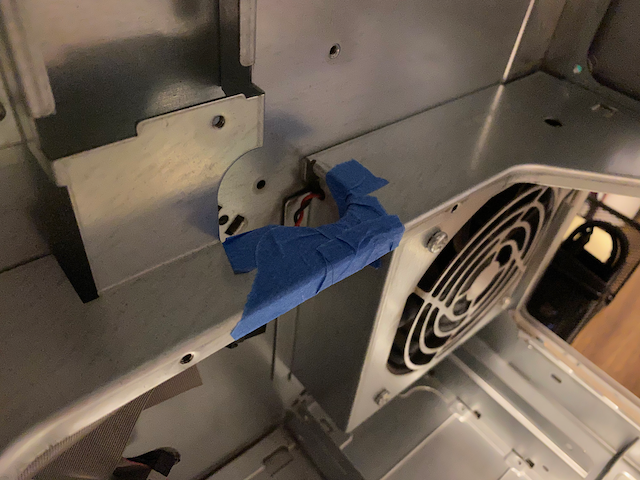

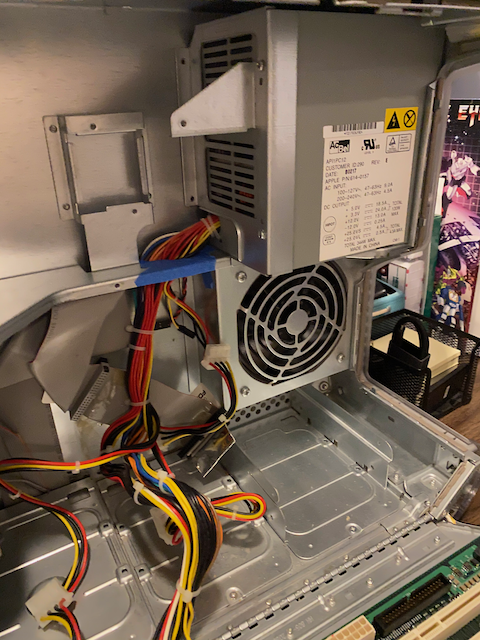

The swing-out chassis makes the PowerMac 7200 very easy to work on. After lifting off the case over, the drive assembly swings up on the right side of the case. A narrow plastic shield over the three PCI slots swings up on the left side of the case. When both pieces are in their open postions, the motherboard DIMM and VRAM slots are directly accessible without the need for tools. This idea of swing-out chassis design would be a tentpole feature of the Power Macintosh G3, G4, G5, and original “cheese greater” Mac Pro tower cases.

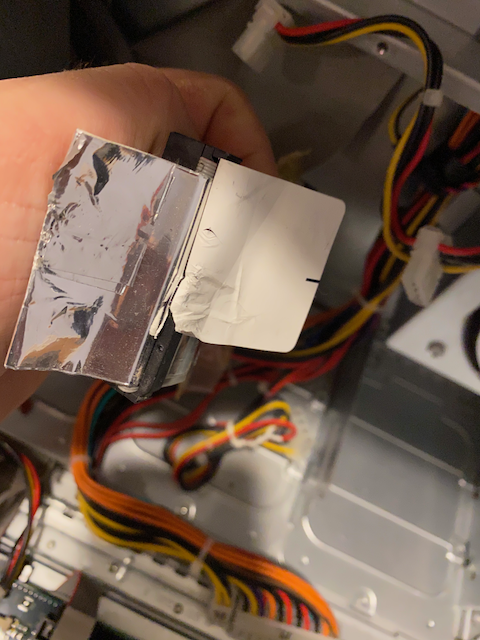

Overall, my Power Macintosh 7200/120 is in fantastic cosmetic condition for its age and runs very well. The previous owner had installed a third-party USB 1.0 PCI card, which makes moving disk images and ISO files over to the machine from my iMac very easy. The Apple Super Drive OEM floppy drive is working remarkably well, and I haven’t had any problems coverting 800kb or 1.44MB floppy disks to image files using Disk Copy 4.2 and 6.3.3. Unlike my attempts to fix the PowerBook G3 Wallstreet, this restoration project was fairly straight forward since there were no electrical problems to troubleshoot.

But, the Power Macintosh 7200, in hindsight, was a solid performer in a sea of beige box machines for die hard Macintosh fans that refused to use MS-DOS, Windows 95, or Windows NT Workstation.